By Dr. Bernardo M. Villegas

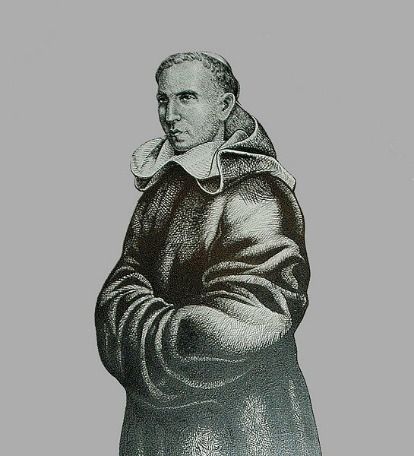

The visit of the King and Queen of Spain on February 11 to 13 was an opportune time to set the record straight about the real pioneers in the defense of human rights in the western world. Whatever abuses might have been committed by some Spanish colonizers in the Philippines and in Latin America, the historical truth is that it was a Dominican friar, Francisco de Vitoria, O.P. (1486-1546), who first developed a full-blown philosophy of human rights and defended the equality of all men and women.

In an article to be published in the Journal of Vera Lex of Pace University in New York, Fr. Joseph de Torre, professor of social ethics at the University of Asia and the pacific, described the role of Francisco de Vitoria in human rights history: “Thoroughly informed and deeply stirred by the briefings from Bartolome de las Casas, who had started his crusade in favor of the Indios after listening to Antonio Montesinos at Santo Domingo in 1511 preach about the violations of the rights of the natives of the newly discovered lands across the Atlantic, Francisco de Vitoria gave a long series of lectures for jampacked audiences at the University of Salamanca throughout the 1530’s. In them, he clearly and courageously stated the fundamental equality of all human beings and the sovereignty of the people given to it by God. He spelled out the inviolable rights to life, to liberty, and to self-rule, including the right to private economic initiative and to participation in public life.”

In the lectures and writings of Francisco de Vitoria, Fr. de Torre points out, “We find the first virtually complete enumeration of all human rights and all the principles of democratic government and law both on national and on international levels, long before the American Declaration of Independence and Thomas Paine’s The Rights of Man.”

“When the reverberation of Vitoria’s lectures at Salamanca reached the ears of Pope Paul III, this Pontiff’s concurrence to his ideas prompted him to issue two Briefs in 1537, authorizing the excommunication of those colonists in the new lands who would dare to deprive the natives of their life, liberty, or property, proclaiming the fundamental equality of all human beings, regardless of their race, religion, or culture. Emperor Charles V’s reaction was to request the Pope to withdraw those briefs of excommunication, pledging that he would as soon as possible promulgate the new laws of the Indies, which would guarantee those rights formulated by Francisco de Vitoria.”

“The new laws of the Indies did come out in 1542, four years before Vitoria’s death, which occurred when the Council of Trent was already in session. This Ecumenical Council, attended by many of Vitoria’s followers, such as Domingo de Soto and Melchor Cano, proclaimed the universality of the Christian religion and of human nature, against both the elitism of the Protestant Reformers and the claims of the racial superiority of the Iberian conquistadores.”

The Spanish thinkers were, therefore, way ahead of the French and the Americans in clearly spelling out the fundamental human rights, which are recognized and respected in every authentically democratic society. We can truly say that King Juan Carlos is an intellectual descendant of those Spanish philosophers led by Francisco de Vitoria in the 16th century. King Juan Carlos is one of the staunchest defenders of democracy in the world today.

I have had the fortune of reading two Spanish bestsellers, one entitled El Rey (The King) by Jose Luis de Villalonga, and the other, La Reina (The Queen) by Pilar Urbano. These two books complement one another in presenting the royal couple in the most human and endearing terms to the Spaniards. Above all, both books confirm beyond the shadow of any doubt that King Juan Carlos played a crucial role in the transition of democracy from the authoritarian rule that lasted 40 years under the late General Francisco Franco.

In the maiden issue of Public Policy, a quarterly journal published by the University of the Philippines, Amando Doronila had words of praise for “the unconditional commitment by the Spanish constitutional monarch, King Juan Carlos, to the democratic transition after the Franco dictatorship.” Doronila’s article was entitled Crisis of Succession. Although he was referring to the crisis our own nation went through during the cha-cha controversy last September, the ideas contained in his article could very well be food for thought for Asian leaders who do not seem to be enthusiastic about a transition to democracy.

Quoting from the book Bourbons of Spain, Doronila described the role of King Juan Carlos as follows: “Although the Bourbon house was reinstalled by Generalissimo Francisco Franco to pave the way for an orderly transition, the king was crucial in saving the transition. On February 23, 1981, when the guardia civil led by Colonel Antonio Tejero seized the Cortes and held the government captive at gunpoint, the rebels contacted the king to win his support. He replied, ‘Over my dead body.’ He phoned the regional commanders, demanding their loyalty. He then wore his military uniform and went on television, pledging that he would protect the Constitution at all cost. The revolt crumbled (The Bourbons of Spain, 1997).”

King Juan Carlos is indeed a paragon of a leader who is sincerely committed to the common good and is willing to undergo untold sacrifices to serve his people. He never broke his word to be “the King of all the Spaniards.” As he himself narrated in the book El Rey, the last words uttered to him by Franco in his deathbed was about preserving the unity of Spain. As the King said: “The unity of Spain was his (Franco’s) obsession. Franco was a military man for whom there were things about which one could not joke about. The unity of Spain was one of them.”

King Juan Carlos, in his characteristic humility, admits that his own experiences in Spain may not be applicable to other countries transitioning from authoritarian leadership to a democracy, especially in the countries of Eastern Europe. As he commented in El Rey, “I have no business giving lessons to anyone, but, in any case, I would first point out the difference between Spain and the old countries of Eastern europe. I would tell them that I inherited a country which had known 40 years of peace, and during those 40 years, a powerful and prosperous middle class was formed, a class that did not practically exist at the end of the civil war. A social class that in no time at all became the spinal cord of the country. I would also tell them that the example of the Spanish king is not exportable to countries which have been economically ruined after 60 years of communism.”

What may not work for East European countries, however, should be a lot more feasible for many East Asian countries that have known at least 30 years of peace and whose economies are much better off than those in Eastern Europe. What these Asian countries need are persons like the King and Queen of Spain who will use their moral authority over their people to rally them around the principles of democracy.

King Juan Carlos is fortunate to have his spouse, Queen Sofia, whom he described as a “great, great professional.” When asked what he meant by a “great professional,” the King simply answered that she takes her job seriously, adding “and God knows that it is not an easy job.”

Queen Sofia has always been inspired by the motto of the royal house of Greece, to which she belonged, being the daughter of former King Paul of greece and brother of former King Constantine: “My strength is the love of the people.” She learned from her parents how to be close to the people, especially those suffering some privation or tragedy. Her royal blood has never kept her aloof from the common folks. When her children were still studying, she was the one who used to drive them to school and to participate in the activities for parents. Even today, Spaniards are still surprised to see the King and Queen caught in traffic just like ordinary people. The Queen values simplicity and sobriety so much that she has always refused to have the traditional ladies-in-waiting that usually surrounded European queens.

The exemplary lives of the King and Queen of Spain, not only as monarch of the Spanish nation but as responsible parents of their three children, make it even easier for Filipinos to appreciate the many good things that we have absorbed from four centuries of contact with the Spanish people. Our celebrating 100 years of independence from the political control of Spain should not prevent us from recognizing that there is so much in our culture that we share with the country whose King and queen we received as our most distinguished royal visitors.

This article first appeared in Universitas in the second quarter of 1998.

Leave a Reply