In the early seventies, I attended a briefing on the Philippine economy organized by the Center for Research and Communication (CRC). This event was my initial introduction to the Institution. At that time, I was the Chief Executive Officer of a company founded by the British to engage in commodity trading as well as investments in other business enterprises. The company, Warner Barnes and Company Inc., has existed for more than 50 years in the Philippines.

I just returned from my German language and management studies in Europe and the United States and had lost touch with Philippine economic developments. The information from the CRC briefing was immensely instructive, useful, and relevant to business executives. I am thankful to Tito Lagdameo and Lito Vitug, my colleagues at Warner Barnes, for introducing me to CRC.

My favorable initial impressions led me to look forward to future activities of CRC. I found the CRC briefing to be professionally organized; the quality of the presentations was notable. I was introduced to Bernie Villegas and Jess Estanislao, who were the principal professionals guiding the Institution and were responsible for leading CRC to public service worthy of admiration.

During the succeeding months and years, I became more involved with CRC activities and eventually became a student in the Master in Business Economics Program (MBE), now known as Strategic Business Economics Program (SBEP). Mike Guerrero and I were the first graduates. Tony Gonzales, Manoling de Leon, and four or five others were also in this program. Looking back, this program touched the heart and minds of many senior executives of corporations in the Philippines. Not only did they become conversant of the Philippine economy, but also became conscious of their social responsibilities—what is known today as corporate social responsibility (CSR).

I found the true value of the MBE program to be beyond economics, in the deepening of my understanding of the Social Doctrine of Church and of the Catholic faith. Father Joseph de Torre, one of our professors, taught me to love philosophy and appreciate the Social Doctrine of the Church. He influenced me the most in this program.

Essentially, I became more conscious of the dignity of the person and, as a result, would try to act in harmony with the message of the Encyclicals that economics must be at the service of man and not the reverse. The dignity of the person is central to the discussions on the nature of profit and just wage. I observed that most of the students in the programs in which I participated were adverse to this idea. I would not be surprised if many of them went home thinking that we at CRC were miserable dreamers.

Being a University of the Philippines graduate, from high school to law school, my understanding of the Catholic faith was not well founded. My studies in the United States and Europe were not helpful either. At the Wharton School, the focus was on economics and management, whose orientations were utilitarian and materialistic in nature.

In various degrees, my classmates in the MBE program were—I surmise except for a few—not far from my level of understanding of the faith. During our post-lecture discussions with classmates who had better Catholic education because they were graduates of schools like Ateneo and La Salle, I noticed that I was not at a disadvantage because of my paltry Catholic education. I realized the advantage of those starting from almost zero over those with distorted biases picked up from earlier education.

As CRC evolved from a research institution to a teaching institution, several degree programs were added to the core program. The core program was the Master of Science in Industrial Economics (MSIE). To this were added MBE, Applied Business Economics Program (ABEP), and a short-lived program in Economic Education designed for teachers. These programs produced graduates who subsequently became key professionals entrusted to run the various schools that the University of Asia and the Pacific (UA&P) established. Among these professionals are Emil Antonio (deceased), Rolly Dy, Peter Lee U, Tonton Torralba , Vaughn Montes, and Omar Cruz. Many other graduates distinguished themselves working for the government, banks, investment houses, and insurance companies, to name a few.

The company I worked for had various branch offices in the south, such as the cities of Bacolod, Cebu, and Davao. As part of my work, I would visit regularly these cities and reach out to my business, social, and family contacts to get them involved in CRC activities, such as briefings, and in the establishment of business clubs that Bernie Villegas initiated. Eventually some of these contacts would attend recollections and circles as they pursued a deeper understanding of the faith. Bacolod City was especially the focus of my attention as I was born and I grew up in Negros Occidental. My circle of friends, relatives, and acquaintances were wider in Bacolod. As time progressed, various activities of a spiritual nature were regularly held in the city.

Sometime in 1980, I joined CRC as a full-time professional after having sold my business as a result of the deteriorating economy under the Marcos government. My responsibility at CRC, as I understood it, was to provide a management perspective to the operations of the Institution. From a traditional viewpoint of management, an institution ought to be led by competent professionals who have the ability to manage human capital and physical resources. Competence necessarily includes the practice of justice. This basic principle guided me to be an active contributor to strategic policy and tactical thinking at CRC.

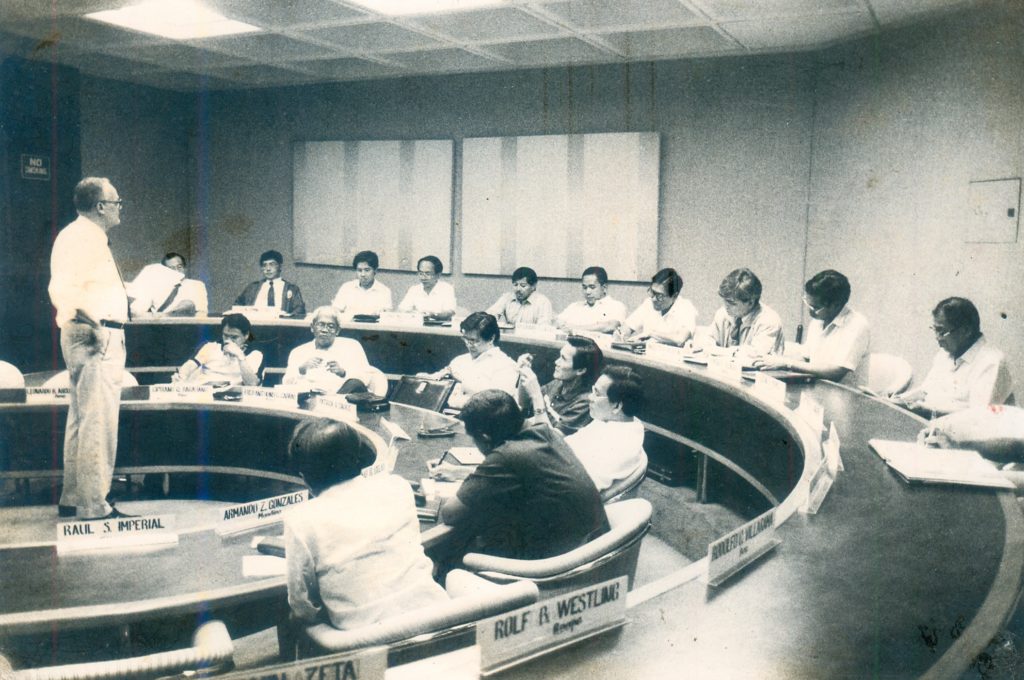

After several months of exposure to the inner workings of CRC, it became clear to me that the strength of CRC was founded on two young economists who were educated in Harvard and had extensive teaching experience. Their management skills, however, had to be reinforced. This is where collegial government became an important consideration. I was new to collegiality; the traditional management style was individualistic. For all its shortcomings, collegiality is probably the best: it draws all the talents of the collegium from a horizontal plane.

The financial situation of the Institution was not stable; revenues could barely cover the cost of operations. If this condition were to last, CRC would have difficulty continuing operations. Fortunately, Jess Estanislao was in the threshold of securing support from a German foundation called Hanns Seidel Stiftung (Foundation). His contacts with the German Ambassador at the time eventually opened the door to establishing a fruitful relation with the German foundation that lasted a considerable period of time.

I was glad to contribute my insights into the German culture, having studied in Germany. I helped provide insights into the German mind that led to a generally smooth and friendly relations with the representatives of Hanns Seidel.

The infusion of funds from Hanns Seidel helped support CRC’s various activities and programs. The stable financial condition allowed CRC to expand its programs and broaden its reach. This was critical to the birth of the University of Asia and the Pacific.

The transfer to Ortigas generated great excitement among the members of the CRC community. The facilities of the Ortigas campus were conducive to more productive work. At the same time, the new campus articulated stability and progress – an important factor in marketing the Institution.

Looking back on all those years at CRC, it is encouraging to note that hundreds, if not thousands, of men and women have passed through the gates of CRC and have been touched by what they learned. At the very least, they opened their eyes to what it means to be Catholic laypersons in the middle of the world.

At present, the name that has become endeared to the business community for many years as worthy of praise no longer pulsates as vigorously. The name CRC, however, continues to have value in the marketplace. It is an asset that UA&P should revive. Although much time has passed from the active days of CRC and market conditions have changed, UA&P must explore with the spirit of innovativeness the opportunities to revive CRC’s brand name.

Dr. Enrique P. Esteban served as Deputy Executive Director (1980-1981) and President (1981-1993) of CRC, facilitating the management of resources during the transition from CRC to UA&P. He became Executive Director of CRC Foundation Inc. from 1996 to 2001 and taught at the School of Management from 2001 to 2011. His wife, Dr. Esther Joos Esteban, a well-loved educator, has been involved in the Institute of Development Education (which paved the way for the now School of Education and Human Development) through its work values seminars that were conducted in key cities of the country. At present, the semi-retired Dr. Enrique Esteban chairs a company engaged in agricultural development in Western Visayas.

Leave a Reply