By Dr. Paul Dumol

The article that follows was the plenary speech delivered by UA&P Associate Professor Dr. Paul Dumol at the Speech Communication Organization of the Philippines’ National Convention on “Asserting Identities in a Globalized/Glocalized World through Speech Communications” held at the Development Academy of the Philippines on May 20, 2011. The speech was first published in the July 2012 print issue of Universitas.

I have been asked to discuss the first objective of your convention: “Analyze how tensions between phases of globalization and glocalization shape and reshape an identity” and this within the larger perspective of the theme, “Asserting identities in a globalized/glocalized world through speech communication.” Looking at this theme and the first objective, I take identity through speech to be a primary concern in this conference, with globalization and glocalization as two sources of pressure tugging in different directions—away from and towards identity.

Allow me to describe the first objective and theme of this convention in terms of a concrete situation: I imagine a Filipino wishing to speak English in a particular way and hesitant to do so, because he may be taken to be other than Filipino by speaking the way he wishes to. There could be a variety of reasons for his wishing to speak in what we may call a “non-Filipino” way: (a) professional reasons (he is working in a call center and should sound “American”); (b) what we might call “academic reasons” (he is convinced the “non-Filipino” way is simply correct English); and (c) rhetorical reasons (he would like to speak directly and to-the-point on a certain topic or to project a particular type of leadership). But whatever the reasons, he feels he runs the risk of alienating his audience and of being accused of “pagpapanggap.”

What I wish to do in this speech is to place the imaginary situation I have just described within the historical perspective of the last 125 years, a relatively brief period of time during which four identities of the Filipino have emerged successively, each the fruit of tension, as the theme of your convention puts it, between globalization and glocalization. These identities have not necessarily been linked to speech, as witness the first that I will now discuss.

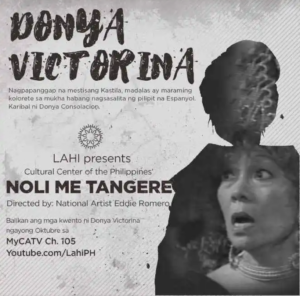

Let me start with a literary character familiar to all of us—Doña Victorina of Rizal’s Noli me Tángere, published 124 years ago in 1887. Doña Victorina is a Filipina who marries an old Spaniard when she herself is “past her prime.” After she does so, she puts away her dresses of piña and jusi and starts to dress like a European. She puts on thick make-up to appear white (no Gluta then!) and curls her hair to frame her brow in ringlets. Rizal pokes fun at Doña Victorina, primarily because she tries to appear to be who she is not. More importantly, within the context of Spanish Philippines she tries to appear to be one of the colonizers and not one of the colonized. If she tried to appear to be Japanese or Indian, she might have seemed ridiculous and nothing more; but because she tries to appear to be Spanish, she takes on a dimension of contemptibility. She is the oldest template in our culture of the would-be denier of Filipino identity, the precursor by almost 70 years of Marcelino Agana’s New Yorker in Tondo.

It is also in the Noli that we read a chapter, not related to the theme of pagpapanggap, but, yes, in some way to the theme of this convention. I refer to chapter 39 (chapter 40 in Guerrero’s English translation), in which the Spanish commandant of the guardia civil in the fictional town of San Diego tries to teach his Filipino wife Doña Consolación how to pronounce “Filipinas” correctly. As you might have anticipated, she pronounces it “Pilipinas.” Unfortunately, the Spanish soldier uses the wrong teaching method, telling her simply to recall that “Filipinas” comes from “Felipe” to which she should add “-nas.” When he has finally gotten her to pronounce the letter F, he is nonplussed when she comes out with “Felipenas.” In this particular case, Filipino identity would seem to be identified with the difficulty to pronounce the letter F.

What I wish to call your attention to is how at the dawn of the Filipino nation the markers of Filipino identity were utterly conventional. In the one case, Filipino women were identified by their native dress, and yet this was a time when Filipino men like Rizal himself could dress like Europeans and not risk ridicule. In the other case, the difficulty in pronouncing certain consonants and vowels in Spanish was identified with Filipinos, and yet there were Filipinos like Rizal who could pronounce all the consonants and vowels of Spanish flawlessly. In 1940, Lope K. Santos put together the first abakada: it did not contain the letter F. Since 10 years ago by one count and 35 by another, the letter F, together with a few others, has been incorporated into the Tagalog alphabet. Virgilio Almario explains why succinctly: Over the years the Tagalog ear and tongue have so progressed, that the Tagalog can now pronounce what the Pampango has for centuries: “Francisco” instead of “Pransisco.”

Around half a century after the Noli was written one of the generals of Aguinaldo, Jose Alejandrino, wrote a book, La Senda del Sacrificio (The Way of Sacrifice). In his concluding chapter he thanked America for extending to us the very same civilization she enjoyed and afterwards criticized her for the same thing. Let me quote from him:

…a completely Western civilization puts us in disadvantageous conditions, as this very civilization is our greatest weakness, considering how we are surrounded by Oriental countries, who have preserved their own practices and customs, adopting from Westerners only those things that make them stronger for the battles of the present and the future.

Alejandrino does not explain why a completely Western civilization in the Philippines would be a disadvantage, but he is obviously thinking in some way of identity, perhaps assuming that we would not understand our Oriental neighbors if we became Western in our thinking or that our Oriental neighbors would refuse to work with us, considering us “aliens.” Twenty years after Alejandrino wrote his book, Nick Joaquin wrote his masterpiece, Portrait of the Artist as Filipino, on basically the same theme: horror at the Americanization of the Filipino and grief at the death of the Filipino culture that characterized the Filipinos of Rizal’s day. Joaquin’s play embodies his critique in the speech of his characters: the main characters and the old senator speak in an English that is Spanish in its accent and intonation, while the villain, Tony Javier, and the two cabaret girls speak English with an American accent.

I believe what we see in the span of time between Gen. Alejandrino’s little book and Nick Joaquin’s three-act play is the demise of a particular version of the Filipino identity and the birth of a new. The old identity was the identity established by Rizal and his generation and continued by their heirs in the first third of the 20th century, an identity focused on patriotic values. The 50s saw the triumph of a new identity, one that looked to America rather than to Spain or Europe, an identity focused, in Nick Joaquin’s view, on making money; the Rizal Law and the Spanish Law were desperate attempts to preserve a heritage. In its wake we had what I would call the Golden Age of Philippine literature in English: Nick Joaquin, N. V. M. Gonzalez, Bienvenido Santos, Gregorio Brillantes, Kerima Polotan. Note, however, that there was no doubt that the Americanized Filipino of the 50s was Filipino, just as there was no doubt that the Hispanized Filipino of the 1880s was Filipino. With regard to Alejandrino’s concerns about our appearing alien to our geographical neighbors in the 1930s, it would seem, in the light of today’s East and Southeast Asia, that we were merely ahead of them in globalizing; today, our neighbors are busy Westernizing: globalization has caught up with them.

Filipino identity changed again in the late 60s. I recall when I was in grade school the increasing importance given to Pilipino as both subject and language: the fines for not speaking in English disappeared; Tagalog versions of school plays appeared; and a Tagalog version of the annual elocution contest in my school was organized. This picked up in high school. The Drama Club was renamed Dulaang Sibol and an annual literary contest in Tagalog was held. This was the time of Agos sa disyerto; the time when new poets in Tagalog, like Rio Alma and Lamberto Antonio, were establishing themselves as the equals in sophistication of their colleagues writing in English. College saw a further intensification of this movement. Speeches were made by student activists only in Tagalog, and courses in Physics in UP and in Philosophy in the Ateneo were offered in Tagalog. A new Filipino identity had arisen, a reaction, we might say, of glocalization, which identified itself with a language, Tagalog a.k.a. Pilipino. This new identity was inspired by nationalism.

I remember telling a friend then that we would be seeing the gradual demise of English and that in 20 to 30 years’ time, English would be replaced by Tagalog as the language of business, academe, and government. How wrong I was! By the late 90s, English was back with a vengeance. The signal was Dulaang Sibol doing Shakespeare in English. This was unthinkable 20 years earlier, and when I heard that Mr. Onofre Pagsanghan was himself teaching English rather than Pilipino, I knew a new Filipino identity was taking shape. Globalization is, of course, behind the resurgence of English, although English, I would say, as a second language, not as first.

By the time I watched Dulaang Sibol’s Macbeth in Shakespeare’s English in the mid-90s, I had changed my sentiments about English and Filipino identity, I who together with some schoolmates had requested the Jesuits to change the medium of instruction in the Ateneo from English to Pilipino in the 1970s. Until the mid-80s, I had accepted the claim that Pilipino gave the Filipino access to Filipino experiences that were simply not available to English-speakers. I accepted the other claim as well that if you knew Pilipino, then you could easily know the other Filipino languages. This, I came to admit, was not true. Half-Ilongo that I am, who never learned Ilongo, I finally admitted to myself that my knowledge of Tagalog gave me only a limited access to Hiligaynon and hardly any to other languages like Pampango or Ilocano. But on the other hand, why should Tagalog, under the guise of Pilipino, be the only vernacular to embody the Filipino soul? This was the time when some claimed that language determined one’s thought and even one’s feelings, when English was accused of being the Americans’ tool for colonizing the very mind of Filipinos. I never believed that, but never questioned it either, but once I did, I saw how ridiculous the proposition was. As soon as I saw that, I found myself asking why Filipino identity should be limited to speakers of Philippine languages. Why couldn’t it be claimed as well by speakers of other languages such as Spanish or English, as it historically had been? The Filipino of the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st, the Filipino who is a relative of OFWs or of children of Filipino immigrants visiting from the United States, England, Italy or Germany, no longer defines himself by a particular language. That, it seems, is a thing of the past.

Let us cast a quick glance back at the Filipino identities that have preceded the present one. The most radical change occurred in the late 60s. I would call the Filipino identity that was being promoted “the nativistic identity,” an attempt to locate a pure Filipino identity by going back to a time preceding our colonizers. But such an identity does not exist: Go back in time before the coming of Legazpi and what you find is not a Filipino identity but an Ilocano identity, a Bicolano identity, a Waraywaray identity, and so on, and underlying all of them an Austronesian identity we share with the Indonesians and the Thais and other peoples of Southeast Asia, Madagascar, and the Pacific. The first Filipino identity that emerged was a mixture bred of globalization and glocalization:

The first two identities— the Hispanic and the Americanized—are variations on the same hybrid identity because hybridity is at the heart of Filipino-ness. Thus, the present identity of the globalized Filipino is a return to the original image of the Filipino: a mixture of the indigenous and the foreign.

Let me now turn to the particular focus of this convention: the invitation to the convention does not articulate concerns involving identity and English, but rather identity and the way we speak English. Here are some of the questions that appear in the invitation: Is the call center agent who cultivates an American accent guilty of betraying his heritage? Is the schwa a betrayal of Asian culture? Is the direct tone a betrayal of Malay courtesy? Please note: language is no longer problematic; the way language is spoken is. Of the various ways betrayal of identity through speech may take place, it is only, in my opinion, the assumption of a foreign accent that would be interpreted in our culture as such a betrayal. The neutral vowel schwa and the liaison of English rhythm are arguably simply valid ways of speaking English correctly. Concise language and direct tone, on the other hand, do make their occasional appearance even in Tagalog, depending on the subject matter and the intended audience, and I have heard assertive responses made in Tagalog.

By “foreign accent,” I mean what a Filipino would readily identify as an American, British, or Australian accent, including, of course, an Indian, Singaporean, or Hong Kong accent. Although hearing a Filipino speaking English with any of these accents might be initially jarring, we would, I suppose, assume that the Filipino in question had picked up the accent in some place abroad where he had lived or studied or worked for some years, but we would truly be surprised if we found out that the Filipino speaking in a flawless American accent had in fact never left the Philippines. Someone from my generation might express strong disapproval of him, but someone from a younger generation might simply conclude that he was a call center agent. But what if there were no professional reasons for the foreign accent? I teach in a school in which some students speak with an occasional American accent or with an American intonation even if they never grew up in the United States. I believe that this is something they probably picked up from television. I have a nephew who has spent all of his young life in the Philippines, and he speaks with a slight American accent and intonation almost certainly from television because neither of his parents speaks with an American accent. Is there a betrayal of Filipino identity here? I think we are in fact seeing the new Filipino—the globalized Filipino.

“Foreign accent”, of course, implies the existence of a Filipino accent; I wish to discuss that now. Eleven years ago, I directed a production of Hamlet with a cast that combined professionals and amateurs. The amateurs, among them the lead actor, were students from our university. After a friend watched a rehearsal close to opening night, he asked me, “Why do they speak in a British accent?” And I replied simply, “I didn’t tell them to.” The cast, including one of the professionals, had simply put it on in the course of rehearsals. My friend replied, “It’s not consistent. Tell them not to.” What accent should they speak in, I asked. And he replied, “Filipino.” “What’s that?” I asked, and his reply was, “The way we speak English.” I knew what he meant from the point of view of theater. He was talking of the way Filipinos performed Shakespeare in the 60s and 70s with neither an American nor a British accent. This was the English of the productions of Fr. Reuter in Saint Paul’s or the Ateneo productions of the late 60s.

What is the Filipino accent? In my day when someone was said to have a “Filipino accent,” this was meant disparagingly. It meant a Cebuano accent or an Ilocano or a Pangasinense accent, an Ilongo or Tagalog accent—a regional accent. The Filipino accent my friend referred to was the English of college students and professors, the English of TV commentators like Bong Lapira, Jose Mari Velez, Tina Monzon Palma—a largely lost generation. This accent could at times sound American, but it wasn’t. The intonation, above all, was not. The Filipino accent my friend referred to was, to Filipinos, English without an accent—neither foreign nor regional.

I have thought about that. Filipino English is English without an American accent or a British accent or Australian for that matter. It does not have a Cebuano, Ilocano, or Ilongo accent either. It is simply correct—at least to Filipino ears. I have always wondered why Filipinos did not adopt the American pronunciation of English while the Americans were around. Was it because they found it hard to imitate their speech? When I was growing up, people would refer to the Arrneow accent. This no longer existed by then, but it seems to attest to a time when at least some Filipinos had an American accent. They must not have been too many. I think Filipinos deliberately avoided having an American accent, opting in the process simply for “correctness.” I imagine they avoided an American accent precisely to avoid becoming linguistic Doña Victorinas: the middle class during the American period, we must remember, was focused on achieving independence. Although middleclass Filipinos loved the Americans, as borne out by their loyalty to them in World War II, they kept their distance from them. (Conversely, now that the Americans are no longer our colonial masters, young Filipinos do not mind sounding American.) In the process we developed a variation of spoken English that is different from any other in the world, a variation that is, however, difficult to pin down. I assume it is the English in which I am talking to you. This is English without the schwa, English that tends to be syllabic, but whose rhythms are marked by liaison, English with the occasional Spanish pronunciation like “sofá” or “menú,” English in which R is always sounded. But otherwise it is hard to describe. Or so I think.

Today’s young generation, the globalized Filipino, is largely unaware of the Filipino accent, and I think this is one reason why he readily takes to an American accent. The other reason, of course, is that youth culture all over the world is today dominated by America. The irony is that people learning English love Filipino English because they understand it so much more easily—whether they are Spaniards or Chinese, Europeans or Asians, Latin Americans or Africans. Nevertheless, the fourth version of Filipino identity we see emerging is not simply the Filipino who speaks English with a slight American accent. If that were all, such a Filipino would be insufficiently globalized, and, like most Filipinos, he is probably insufficiently glocalized. Let me explain what I mean.

Three weeks ago, I was a speaker in a seminar for high school teachers on civic education, and during the Q&A one of the teachers explained her problems. She taught in Matnog, a municipality of Sorsogon that faces the Visayas and that consequently has multiple variants of Bicolano: Bicolano laced with Tagalog, Bicolano laced with Waraywaray, Bicolano laced with Bisaya, Bicolano laced with Hiligaynon. Besides, there are migrants in Matnog from Mindanao and visitors from Capul who speak their own language different from the other languages in Samar. How is one to communicate to students from such different backgrounds?

A teacher from East Las Piñas replied to her. This teacher said she was from Masbate, and Masbate, like Matnog, is exposed to fishermen and traders from Luzon and the Visayas. There was nothing else to do but learn all the languages spoken in Masbate. It turns out that she was married to a Maranao, and she demonstrated how she learned Maranao during the time she was assigned to Marawi. She was a polyglot, and she spoke beautiful English. I recall a similar anecdote from my aunt, then a professor in UP, from the early 70s: her friend, Miss Ching Dadufalza, and a colleague were riding a jeepney on the UP campus, chatting away in English, and a student in the same jeep gave them a scowl and muttered something derisive about their speaking in English. Both teachers were, I believe, English teachers. Miss Dadufalza turned upon the student and berated her in perfect Tagalog from the Golden Age of Quiapo Tagalog and afterwards switched to equally perfect Ilocano, politely asking her how many Philippine languages she knew.

Listening to the teacher from Masbate and recalling the anecdote about Miss Dadulfalza, I thought this is the Philippines: multiethnic, linguistically vibrant and dynamic, with citizens who know more than one Philippine language and more than one foreign language, people quite undeniably globalized and quite undeniably glocalized at the same time.

Let me attempt a description of the Filipino of the 21st century, the heir of Rizal’s Crisóstomo Ibarra, Nick Joaquin’s Bitoy Camacho, and the student activists of the 70s. The Filipino of the twenty-first century is (or should be) the master of more than one Philippine language and more than one foreign language, in effect both globalized and glocalized. In addition, he is (or should be) the master of more than one accent and intonation for speaking English, so much so that he can be an American to Americans, a Britisher to the British, and a Singaporean to the Singaporeans. And his platform for globalization is Filipino English—English without an accent, but correctly pronounced, which brings us to a characteristic of Filipino English. It is flexible: before an American audience the speaker can easily Americanize it; before a British audience the speaker can easily Anglicize it. This convention is focused on multicultural environments. Well, the best way to reach such an audience is precisely through Filipino English: everyone understands us! Perhaps that is the challenge to speech experts like you: to call attention to Filipino English and sing its praises, to study it and teach it, but not as a mold but as a platform from which to further shape English into the variant that would connect to the specific audience. For the Filipino of this century, language and the way it is spoken is a tool, not a marker of identity. So what would the marker of Filipino identity be, linguistically speaking? Precisely his mastery of multiple languages, accents, and intonations.#

Banner photo by Christopher Camitan.

Leave a Reply