(This article first appeared in the October 1996 issue of Universitas.)

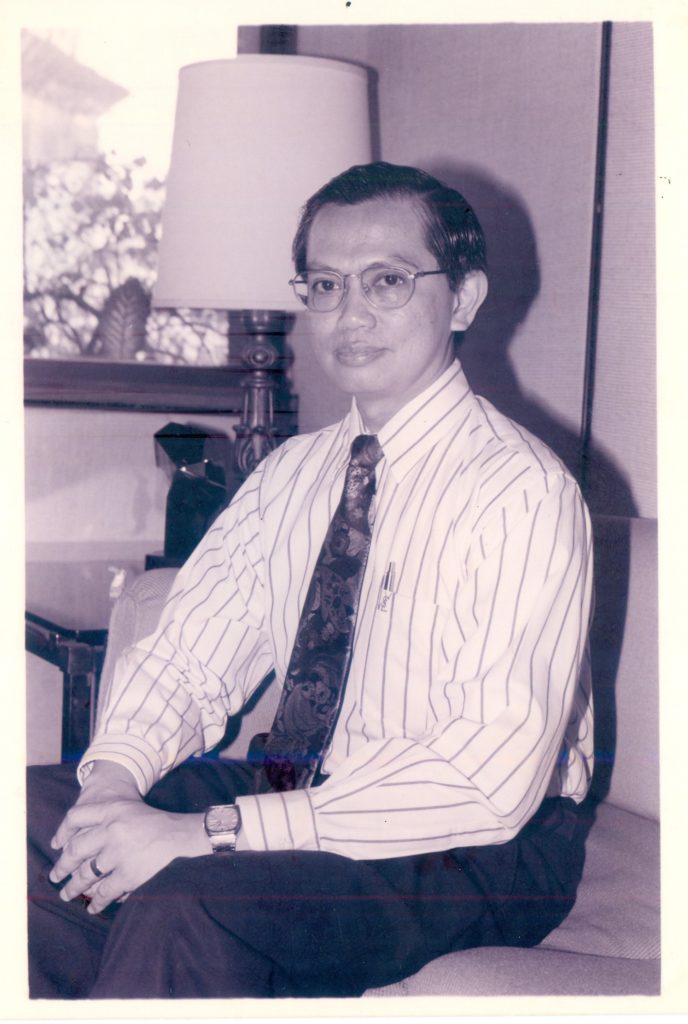

Since an early age, Paul Dumol has known the consequences of creativity.

From the time his first play—Ang Puting Timamanukin (co-written with Gil Quito and published in 1968)—sprang at Ateneo High School’s Dulaang Sibol, Dr. Dumol has felt the joy of success and the pressure of trying to surpass himself. “The pressure was mainly self-generated, and I dealt with it the best way one can—by trying.”

A proof of that effort was Ang Paglilitis ni Mang Serapio, whose first production in 1969 was directed by the playwright himself and which has become one of the most-performed plays in Philippine theater.

Dr. Dumol, now UA&P’s Vice President for Academic Affairs, notes the greater maturity his writing has attained and still talks with reverence about the influences that shaped his style: William Shakespeare (“the style of play which has many scenes”) and Bertolt Brecht (“especially his alienation effect”). In working on a play, he says, “I rely on the opinion of close friends, and I monitor the production, from rehearsals to the first run.”

Most recently, his Mga Texto at Komentaryo, was staged by CCP’s Tanghalang Pilipino. After devoting almost five years to academics, did he have any difficulty bringing another play to the stage? “No,” he says, “because Texto is a documentary play and the work consisted mainly in choosing the [source] documents and editing and translating them. This was much easier than having to write a play from scratch, where, to do which, I have to figure everything out – from the plot, the narrative, the dialogue, and so on.”

In writing a play like Texto, the respect for facts is his foremost consideration. “I was tied down even to the actual dialogue. There’s very little I could do,” he says with the humility of one with an unequivocal love of history. His other history-based works, through, such as Francisco Maniago (1988) and Pule (a monologue on the life of Apolinario Mabini; 1989) had “a fair share of fictionalizing in them,” which was allowed by the nature of the issues they were trying to address.

Using Filipino as the medium in all his plays makes Dumol’s body of work distinctive. He uses the language for practical reasons. First, “because it is the language Filipinos use for nonformal topics, and plays normally feature nonformal topics…” and second, because it “avoids the inconvenience of Filipino actors speaking English in a variety of accents.”

Dumol has made complicated decisions related to his art. In 1974, he removed Kabesang Tales from production, fearing the play might be seen as a critique of friars in 19th-century Philippines instead of the real issue: the administration of justice. He has considered rewriting the play to avoid any such misperceptions but believes “there is nothing ideologically, philosophically, or theologically mistaken in the play. When I die, certainly, it will be there for everybody to stage as often as they might want to.”

A writer’s block that lasted for seven or eight years until he wrote Felipe de las Casas (1983) may well have been the source of his greatest anxiety. “It was the fear of not having anything to say which was original or personal, of not having something to write about in a deep sense.” The fear still occurs whenever he finishes a play, but not as strong as it was more than 20 years ago. “Now, if there’s nothing to write about, I tell myself I won’t write.”

When asked what he thinks about the current Philippine theater scene, he playwright weighs his response. And he cites a problem: the lack of awareness of Metro Manila audiences about plays and musicals written and produced by Filipinos. “I imagine the production at UP and Ateneo would have a good crowd of students, but I don’t know how many professionals or office workers watch plays.” Theater location and production costs often influence the behavior of the public and the feasibility of stage productions. For a theatergoer in the metropolis, watching a play usually means having to suffer the inconvenience of traffic. For theater groups, generating interest among potential audiences means spending on promotions, not to mention finding accessible venues. He says “it would be much easier (for a theater company) to build a regular clientele if people knew where the theater company stages its production and when its season is.” The situation may be different in the provinces, though. “In the Visayas,” he observes, “the musicals of Rizal’s novels have always performed to SRO audiences.”

Ilustrado, his upcoming musical on Rizal’s life and a collaboration with Ryan Cayabyab, will again show how well the artist and the scholar in Paul Dumol work together. The scholar guides him in “using historical facts as parameters, [a task] which helps the imagination come up with something original, not something which one thinks is original but is actually a pastiche of the different things one has read and seen and the effects one wants to produce.” In most of his works, which are a combination of history, philosophy, and literature, the artist “makes me more sensitive to the words and expressions [in source texts and documents] in a way that a scholar is not.”

But maybe it is the scholar that helps Paul Dumol realize the responsibility of an artist: that “of sincerity and honesty. It’s the responsibility of giving his audience a fresh view of truths about human nature, life, society, existence. This freshness can be discovered not by a playwright alone but by any artist through a careful consideration of his experiences and that of others, sifted through his heart and mind.”

A good account on Paul Dumol, the wonder kid of my generation.