By Father Peter Edward Cabreros[1]

What is interreligious dialogue? It’s Kerygma 3.0.[2] How does the Catholic Church engage in such dialogue? As the First Christians did. Whaaat?!

Two recent documents explain the answers. One is foreign; the other is local. Both serve as frameworks to understand the value of interreligious dialogue.

The foreign one refers to a place: Abu Dhabi. A year has passed since this contentious document was signed by Pope Francis with the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar, Ahmad Al-Tayyeb officially called the “Document on Human Fraternity for World Peace and Living Together“[3] (4 February 2019). Some widely hailed it as a milestone, not only regarding relations between Christianity and Islam, but as a blueprint indicating the way to a culture of dialogue and collaboration between faiths. In contrast, others consider it as going against – or at least muddying up – the tenets established by the Church in dealing with other world religions in spreading the Good News. At the center of it all is its statement: “The pluralism and the diversity of religions, color, sex, race and language are willed by God in His wisdom, through which He created human beings”.[4]

The bone of contention is whether any dialogue desired by the document acknowledges basically how the First Christians did it back then. It’s an approach characterized by what St. Josemaría Escrivá calls the “apostolate of friendship and confidence”. BUT IT IS AN APOSTOLATE OF FRIENDSHIP AND CONFIDENCE ON THE LEVEL OF THE NATURAL MORAL LAW IN THE RECOGNITION, PROMOTION AND PROTECTION OF THE COMMON GOOD.[5]It is a dialogue carried out by a Christian that is faithful to the Good News while openly, sincerely and respectfully seeking the truth and likewise openly, sincerely and respectfully dealing with their fellow human beings — Jews or Gentiles. Convinced that sharing the Good News in words and deeds would eventually lead these people they deal with to freely and willingly seek conversion to the Christian Catholic faith.

This paper is not a critique on the abovementioned document. Rather, it serves to illustrate the minefield of controversies that must be dealt with and the pitfalls that should be avoided concerning the Catholic Church’s role in interreligious dialogue here and now.

The second local document is part of the novena (nine-year) preparation for the 500th Anniversary Celebration of the Proclamation of the Good News in the Philippines in 2021. This year, 2020, has been declared by the Catholic Bishops Conference in the Philippines (CBCP) as the Year of Ecumenism, Interreligious Dialogue and Indigenous Peoples. Last December 1, 2019, it issued its Pastoral Letter that states to follow the tenets of the abovementioned Abu Dhabi document and proposes four fundamental forms of dialogue as guides. Before we delve on the specifics of this pastoral letter, let us define terms[6].

Ecumenism[7] is the apostolate[8] carried out by Catholic Christians in the form of dialogue with other non-Catholic Christians to encourage and convince them to return to the unity of faith found in the Catholic Church. Interreligious Dialogue is the apostolate carried out to promote mutual understanding, respect and collaboration between Catholics and the followers of other religious traditions or world religions.[9] Each apostolic endeavor is managed separately by the Holy See. Ecumenical dialogue is the task assigned to the Pontifical Council[10] for Promoting Christian Unity (28 June 1988). Interreligious dialogue is handled by the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue (19 May 1964 then known as Secretariat for Non-Christians and renamed in 28 June 1988). There is one dicastery that deals with apostolate with non-believers, the Pontifical Council for Culture.[11] What about those who were formerly from Christian environs that has since been secularized[12]? It is the Pontifical Council for Promoting the New Evangelization (28 June 2010).

What about the Indigenous Peoples? The main concern is implementing inculturation[13] properly. Within the Philippine context, “inculturation is an expression of dialogue with indigenous people’s faith communities. Through inculturation, the church makes the gospel incarnate in different cultures and at the same time introduces peoples, together with their cultures, into her own community”.[14]

What are the four forms of dialogue proposed by the CBCP? They are listed here without any order of priority:

- The dialogue of life, where people strive to live in an open and neighborly spirit, sharing their joys and sorrows, their human problems and preoccupations;

- The dialogue of action, in which Christians and others collaborate for the integral development and liberation of people;

- The dialogue of theological exchange, where specialists seek to deepen their understanding of their respective religious heritages, and to appreciate each other’s spiritual values; and

- The dialogue of religious experience, where persons, rooted in their own religious traditions, share their spiritual riches, for instance regarding prayer and contemplation, faith and ways of searching for God or the Absolute.

It would do well for each of us within and from the university to consider how to foster such forms of dialogue, individually or as a group, to help prepare all for this auspicious half-millennium celebration of Christianity arrival in our country. It’s since been dubbed as “500YOC” with “Gifted to Give” as its theme. Benedict XVI, early in his priestly and scholarly life, espoused the belief that Christians are “the few for the many”. Indeed, God gifted us Himself to enable us to give Him – and ourselves – to others. Interreligious dialogue plays a big part in this task.

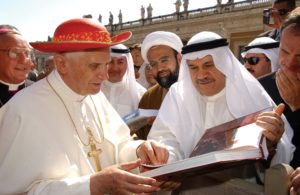

Credit: L’Osservatore Romano

Ultimately, it is best that one reads and analyzes both documents on one’s own. Perhaps these tenets that Benedict XVI identified can serve as guides for one to arrive at a fair assessment. They serve as aids in this divine directive where the interplay between fidelity to the Gospel proclamation (kerygma) and fostering openness to a dialogue of truth and love among people of different creeds is harmoniously preserved and the pitfalls of a misguided dialogue are avoided. But such dialogue will only be effective if both parties are open and sincere — hallmarks of the apostolate of friendship and confidence St. Josemaría taught. They are six assertions that participants – especially the Catholic faithful – must uphold while engaging in a dialogue of any type[15]:

- Faith and reason are both respected shown in both parties’ open and sincere quest for the truth of the meaning of human existence;

- Willingness to undergo a conversion (metanoia) – a prerequisite to education in truth;

- Education in truth that leads inevitably to a personal encounter with Jesus Christ, the God-man;

- This encounter encourages communion with His Mystical Body fully embodied in the Catholic Church magisterially (teaches the truths) and mysteriously (asks for obedience of faith);

- This communion consolidates apostolic zeal that attracts all towards a full and active participation in unity-in-communion lived in the Christian life of prayer, recourse to the sacraments and deeds of service motivated by love; and

- All these assertions give priority to humble, pious prayer; to a true witness of an upright life, and to a deep respect for the freedom and dignity of all men.

These are the traits of an effective interreligious dialogue that Benedict XVI identified and what St. Josemaría called the apostolate of true friendship and open confidence: to propose but not impose; to convince but not coerce accompanied by good example and upright moral behavior.

Interreligious dialogue done this way is apostolate ad fidem (towards the Faith). If we really think about it, when the first Jewish Christians started preaching the Good News to the Gentiles, that was interreligious dialogue at work then. This is essentially the same task that we ought to continue to carry out now.#

—

[1] The author is a Roman Catholic priest of the Prelature of the Holy Cross and Opus Dei whose doctoral dissertation at the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross in Rome (2009) addressed the matter of interreligious dialogue according to the vision of Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI.

[2] Kerygma means “spreading the Good News” or “to evangelize”; 3.0 refers to the Third Millennium, i.e., now.

[3] It is more commonly known as the Abu Dhabi Document.

[4] Underline added for emphasis. In a nutshell, the controversy is whether Pope Francis meant by “Will of God” to refer to God’s Positive Will in which case the document will be problematic. But if he referred only to God’s Permissive Will, then it is acceptable though it could have been phrased more clearly. Even in this regard, critics still contend that the latter explanation is not enough or even valid. This is another story.

[5] Common good is defined as “the sum total of social conditions which allow people, either as groups or as individuals, to reach their fulfillment more fully and more easily.” [Vatican II, Gaudium et spes, 26; cf. Catechism, 1906]

[6] Kindly refer to the footnotes for other terms defined not found in the main body.

7 “Ecumenism”, as the CBCP pastoral letter explains, “refers to the various efforts, movements or tendencies to come together by Christians of different Church traditions, journeying toward worldwide Christian unity or cooperation. Ecumenism comes from the Greek word ‘oikoumene’ meaning, ‘the whole inhabited world’ searching for unity among Christians (Eph 4:3)”.

8 The author firmly believes that any endeavor carried out by the Church and her faithful in dialogue with other faiths is fundamentally apostolic when done properly.

9 In this regard, the major religions especially identified by the Church are Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism. What about Judaism? St. John Paul II highlighted the unique relationship the Christian Faith has with the Jewish Faith. A special and separate pontifical commission called the Commission for Religious Relations with the Jews was thus established in 22 October 1974 that works alongside the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity.

10 Pontifical Councils are the fourth tier (mid-size departments or dicasteries) in the Holy See’s governing structure having special functions in connection to ecclesial life deemed of primary importance by the pope. As such, they fulfill their duties in the pope’s name and by his authority. With the recent reorganization of the Roman Curia by Pope Francis, eight (8) exist of which those not mentioned above are the Pontifical Council for the Laity, Family and Life ( formerly three separate pontifical councils now combine into one since 15 August 2016); for Integral Human Development (combined four previously separate pontifical councils of Justice and Peace, Pastoral Care of Migrants and Itinerant People, Health Care Workers, and Cor Unum established last 17 August 2016); for Legislative Texts (15 September 1917) and for Social Communications (17 September 1948).

11 Since 1993, it acquired under its jurisdiction the former Pontifical Council for Dialogue with Non-Believers.

12 “Secularized” refers to a process in which religion loses social and cultural significance often leading to detrimental effects on society as the role of religion in society becomes restricted and religious faith is ignored or worse, ridiculed and even persecuted. It is synonymous to “laicized”.

13 “Inculturation” is the adaptation of Christian teachings in a non-Christian culture and the influence of these cultures on the evolution of Christian teachings.

14 CBCP Pastoral Letter for the Year of Ecumenism, Interreligious Dialogue and Indigenous Peoples (1 Dec 2019).

15 Whether it be ecumenical, interreligious, with non-believers, with secularized/laicized people or with indigenous communities.

Note: This article was part of the lineup for the May 2020 issue of Universitas, which aimed to tackle the importance of dialogues. The magazine had to be modified, however, due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Banner photo by Paul Haring (Catholic News Service)

Leave a Reply